strace with Navi

Diving into navi as an interactive command builder, and using strace as a

demo for concise cheat sheet!

In the previous post I spent a short time detailing steps I take to make my

command line experience more pleasant and efficient. One of the steps I listed

was using the tool navi to quickly recall

commands.

This is incredibly helpful for commands that I don't use often, or for

variations of commands with specific options that I use less frequently. I find

fuzzy searching through my navi cheats is 100x faster than grepping through

Manpages or --help output. Now, of course there are times where my navi

cheats don't cover something I need and I must fall back to older methods, but

then I just update my cheats and go about my day.

I recently found a new (to me) way to use navi, as a "command builder" of

sorts. It makes sense to use on commands where the flags/options are additive,

and not individual commands (which is somewhat of a pet peeve of mine...)

Future Kevin SaysI should make a post on CLI UX about why certain CLI patterns are sub-optimal...¯\(°_o)/¯

Enter strace

A good example is strace, which allows one to display system calls made by

particular commands and processes. Several other blog posts have recently

mentioned strace, and it's a tool that has come in hand for me more than a

couple times so in it's honor it'll be the demo today.

We won't be adding all the options that strace has, but the ones I find most

common to my use cases, which probably covers a pretty vast swath of people as

well.

Our goal is to build a navi cheat sheet that walks us through building an

strace command with all the options we want to expose.

This post won't cover all the details of strace or even what all the options

mean, although most of the ones we're adding are pretty self explanatory.

Future Kevin SaysLike a good CLI should be!(ᕗ ͠° ਊ ͠° )ᕗ

For a pretty good summary, see "strace The Sysadmins

Microscope".

navi Overview

As mentioned in my previous post, I bind navi to <CTRL>-n in my terminal,

using the following ZSH function in my ~/.zshrc:

_call_navi() {

local selected

if selected="$(printf "$(navi --print --path ${HOME}/Projects/navi-cheats/cheats </dev/tty)")"; then

LBUFFER="$selected"

fi

zle redisplay

}

zle -N _call_navi

bindkey '^n' _call_navi

The post important parts are the --path argument, which tells navi to look

in a specific location for cheat sheets (I prefer to use my own directories,

instead of the built in ones and "adding repos" feature). You can add multiple

directories separated via : (and technically I have a few directories,

including a $work one that I pulled out of the example above).

The path listed above is the cheats/ directory of my public

repository. It's just a big list of

.cheat files. More on that soon.

Also the --print flag tells navi to simply print the final command, instead

of running it. This is useful because often I want to make some additional edits

to the command that either my cheat sheet didn't account for, or the features

simply don't exist to add the flexibility I wanted.

Normally, --print would just print the command to stdout, however with ZSH

you can have the current command line replaced by the output of a command, which

is what is happening the remainder of the function.

What is a .cheat file?

navi looks for files ending in .cheat with a particular structure. I won't

re-hash the entire tutorial from the navi

repository

since it's quite good and comprehensive, but the TL;DR is:

.cheatfiles can be split up and named however you like, as the file names aren't used bynavi. I tend to use either command names or situations as file names.- Lines starting with

;are ignored (comments) - Lines starting with

%are categories and comma separated key words. These make good "tags" when fuzzy matching. I tend to use command names, or variations of the names to assist with matching. - Command descriptions are lines starting with

#and used as a short description of a command - Commands templates are on the line below a description with no leading

characters.

- Commands templates can be multi-line with

\like regular shell commands - KEY Commands templates can have "variables" that get expanded later if

the command is selected. Variables are words surrounded by angle brackets

(i.e.

<foo>)

- Commands templates can be multi-line with

- "variable expansions" are optional, but are lines that start with

$followed by the variable name, then:followed by the command to expand the variable (i.e. the command to present options to user for selection). So our<foo>variable could have an expansion$ foo: echo -e "true\nfalse"which would present the two optionstrueandfalseto the user usingfzf, then whatever the user selected would replace the<foo>in the command template. - If no variable expansion line is provided, an

fzftext box is presented to the user allowing them to type whatever they want, which will replace the variable in the template. - Files can have as many "categories" as you like

- Multiple command templates can share a single expansion. I.e. think of of a

bunch of firewall commands, all of which need to allow a user to select a port

number. All firewall template command could list a

<port>variable, and the file would contain a single$ port: ...expansion that applies to all templates. - Beyond functioning as tags, categories separate out variable expansions. So variables expansions only apply to command templates within the same category.

So a typical .cheat file follows this kind of a pattern:

% foo, bar

# Description of command

command -f -b <qux>

# Description of other command

other_command -b -z <bar> <foo>

$ bar: ...

$ foo: ...

Again, a single .cheat file can have multiple % categories, splitting up the

expansions, to allow you to re-use variable names with different concrete

expansions. Although, I normally only have a single % per file.

Variable Expansions

This is where the true power of navi comes in to play. By default, navi

presents a blank fzf text box for variables without an expansion line. Such as

the <qux> variable above.

So let's first build out our first strace .cheat file:

% strace

# Display system calls for a command

strace <CMD>

Running navi, and typing something in the fuzzy match area to select our

strace command then brings up a new screen asking us to fill in the CMD

variable (since we did not provide an expansion). If we type firefox, navi

drops us back to the terminal with the following command ready to run:

$ strace firefox

Static Expansions

We can present a limited set of options for the user (which by default also allows them to type something outside of our presented options).

So if we instead add the following line below our command template, we'll get a list of two options.

$ CMD: echo -e 'firefox\ngoogle-chrome'

NOTE: the user can still type something outside of our two options, although we can prevent this behavior which we'll see in a minute.

Since fzf by default delimits options via a newline \n, we can actually make

the expansion a little more readable using spaces, since the values themselves

don't have any spaces.

$ CMD: echo 'firefox google-chrome' | tr ' ' '\n'

This is functionally equivalent to what we had before, but some prefer it. It

also points out that expansions can use standard pipes |.

Let's add a new command (with description) to our file:

% strace

# Display system calls for a command

strace <CMD>

; 👇 is new

# Display system calls for a single PID

strace -p <PID>

$ CMD: echo 'firefox google-chrome' | tr ' ' '\n'

Now we can type out a PID we wish to attach strace to.

But there is a problem; since we didn't provide an expansion, it's up to us to

type in a valid PID. For example, typing foo just blindly makes our command

line:

$ strace -p foo

Which will error when run.

Using a static expansion can help with this somewhat:

NOTE: on 64bit systems PID_MAX_LIMIT is around 4 million...but for

simplicity and demo sake we'll make it the 32bit limit since we'll be changing

it shortly anyways.

$ PID: echo {0..32768} | tr ' ' '\n'

Which is better, we'll get a huge list of numbers (that we can fuzzy match through). And we'll be dropped on the command line with a PID:

$ strace -p 28267

But we still have the problem of someone can just type foo and again we're in

invalid territory.

navi provides a delimiter we can use on the variable expansions --- to

provide additional context navi either about the selection itself, or

presentation of the options. One such option is --prevent-extra which limits

the user to list of options you provided, and nothing more.

NOTE: --prevent-extra is listed as experimental. And when user provides

something outside the presented list, navi exits with an error. I'm on the

fence about if that's better or not. But it's an option no less.

Changing our expansion to the following solves the invalid issue we had before:

; 👇 is new

$ PID: echo {0..32768} | tr ' ' '\n' --- --prevent-extra

Dynamic Expansions

That crazy list of PIDs with no context isn't a ton of help either. Luckily

navi can come up with options dynamically!

So instead of just providing 32,000 numbers in sequence, with no process names,

or even knowing if its a valid PID of a current process we can just ask navi

to look at the currently running processes via standard shell commands and

present those to the user.

But we have a slight problem, something like ps -aux prints out far more

information than we need. We need a PID and a name, more or less.

Since navi expansions are just shell pipes, we can use standard utilities like

grep and awk to fix that!

$ PID: ps -aux | grep -v PID | awk '{print $2" "$11}' --- --prevent-extra

We leave the --prevent-extra because we're still limited on if the PID isn't

present in this list, well its not valid.

Now we get a nice fuzzy match-able list of PIDs and the associated processes!

However, running this shows one more issue...we get the whole selection on our command line:

$ strace -p 3860 /usr/bin/firefox

NOTE: the extra spaces in there come from our expansion option too!

navi options to the rescue again! There is a --column option which allows us

to use only a single column of output as the final selection!

Changing our expansion to:

; 👇 is new

$ PID: ps -aux | grep -v PID | awk '{print $2" "$11}' --- --column 1 --prevent-extra

Gives us the correct output.

$ strace -p 3860

Much better!

Additive Options

Ok, so we can now build an strace command, fuzzy match through a valid list of

processes running on our computer, but strace provides all kinds of additional

options for us. For example, what we want to suppress attach/detach messages

(i.e. -q), or it's variations (-qq or -qqq)?

Turns out, we can use expansions for that too!

Changing our command template slightly, to add a placeholder for the -q|-qq|-qqq:

# Display system calls for a single PID

strace <QUIET> -p <PID>

We can then add another expansion this variable:

$ QUIET: echo -e '\t\tNo suppression;-q\t\tSuppress attach/detach messages;-qq\t\tAlso suppress exit statuses;-qqq\t\tSuppress every suppressible message' | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1

We're just building off what we already know. Splitting options into two columns

with the flag we want to add on the left, and description on the right,

separating all options with ; which we can replace with a newline via tr,

then telling navi to only use the first column as the actual selected output

for the expansion.

Now we get a new screen asking us if we want to suppress messages or not, with the associated option on the left!

PRO TIP: It's a good idea to place the "none" or "no" option that represents

no additional flags first, as the user can then just fly through pressing

<enter> when they don't wish to add anything additional. This greatly helps

when there are a bunch of optional flags.

One final nicety I like to add is the --header option, which allows one to

give a short text describing what the user is actually selecting. This comes in

handy sometimes when the choices aren't super explanatory.

So our final expansion version becomes:

$ QUIET: echo -e '\t\tNo suppression;-q\t\tSuppress attach/detach messages;-qq\t\tAlso suppress exit statuses;-qqq\t\tSuppress every suppressible message' | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Suppress any output?"

This shows a text message above the input box with description of what navi is

asking.

We can continue fleshing out the options repeating the above steps for the flags we want to present.

Here is more complete set of expansions:

# Display system calls for a command

strace <SUMMARY> <QUIET> <FOLLOW_FORKS> <SYSCALL_TIMES> <SUCCESS_FAILED> <DECODE_FDS> <CMD>

; 👆 these variables are new

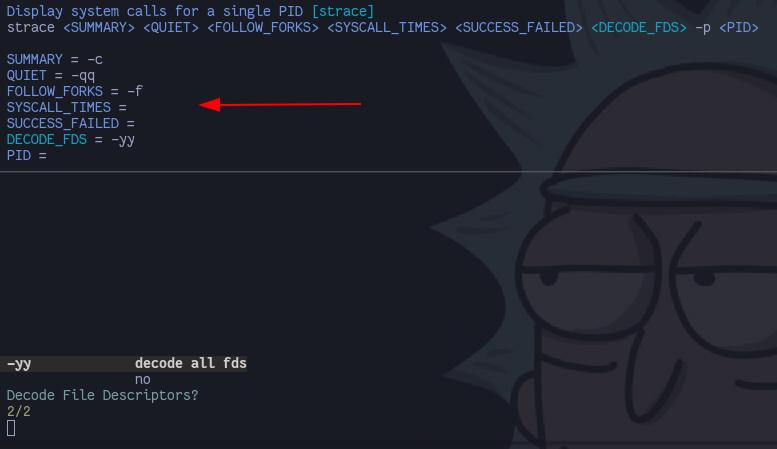

# Display system calls for a single PID

strace <SUMMARY> <QUIET> <FOLLOW_FORKS> <SYSCALL_TIMES> <SUCCESS_FAILED> <DECODE_FDS> -p <PID>

; 👆 these variables are new

$ PID: ps aux | grep -v 'PID' | awk '{print $2" "$11}' --- --column 1 --header "PID to attach to?"

$ QUIET: echo -e '\t\tNo suppression;-q\t\tSuppress attach/detach messages;-qq\t\tAlso suppress exit statuses;-qqq\t\tSuppress every suppressible message' | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Suppress any output?"

; 👇 These expansions are new

$ TIME_STAMPS: echo -e "-t\t\tabsolute;-tt\t\tabsolute usecs;-ttt\t\tabsolute UNIX time" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Print Timestamps?"

$ SUMMARY: echo -e "\t\tnone;-c\t\tsummary;-C\t\tsummary only" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Print Summary?"

$ FOLLOW_FORKS: echo -e "\t\tno;-f\t\tfollow forks;-ff\t\tfollow forks and split output" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Follow Forks?"

$ SYSCALL_TIMES: echo -e "\t\tno;-T\t\ttime spent in syscalls" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Display time spent in syscalls?"

$ SUCCESS_FAILED: echo -e "\t\tdon't filter;-z\t\tsuccess only;-Z\t\tfailed only" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Filter success or failed exits?"

$ DECODE_FDS: echo -e "\t\tno;-yy\t\tdecode all fds" | tr ';' '\n' --- --column 1 --header "Decode File Descriptors?"

Now that we'll have more expansions, you'll notice that in the upper section of

the navi window, there is a preview of what expansions have been expanded to

thus var. This comes in handy at times.

Limitations

This brings us to one of the limitations of navi (thus far), in that it's

difficult to see if a previous variable has been expanded into something or

another. There is variable

dependencies

but those don't quite do what I want.

A good example is the next (and probably most important) option for strace and

that is the filtering.

For example, so see all syscalls related to processes (such as execve(2) for

when a process is created), you could use:

$ strace -e trace=process ...

The -e option takes expressions in the form of option=value. There are quite

a few predefined options, as well as values, groups, etc.

The way navi works now, you can't for example ask, "Do you want to add an

expression" and insert -e foo=bar or nothing if they answer no. So we end up

with two different command templates, one with expressions and one without.

Additionally, navi is limited to a single expression, you can't for example

loop and provide multiple expressions. navi does provide a --multi option

which allows FZF to pick multiple options from the list (i.e. imagine multiple

firewall ports), but not multiple pairs in the syntax strace expects. This is

normally fine, as you can always add additional expressions after navi is

finished, and many times a single expression is all you want anyways.

To get a better sense of this, we'll add two more command templates, adding

expressions, and navi provided lists for the options and values pairs:

# Display system calls for a command (with a filter)

strace -e <EXPR_OPT>=<EXPR_SET> <SUMMARY> <QUIET> <FOLLOW_FORKS> <SYSCALL_TIMES> <SUCCESS_FAILED> <DECODE_FDS> <CMD>

; 👆 the -e variables are new

# Display system calls for a single PID (with a filter)

strace -e <EXPR_OPT>=<EXPR_SET> <SUMMARY> <QUIET> <FOLLOW_FORKS> <SYSCALL_TIMES> <SUCCESS_FAILED> <DECODE_FDS> -p <PID>

; 👆 the -e variables are new

$ EXPR_OPT: echo 'trace abbrev verbose raw signal read write fault inject status quiet kvm decode-fds' | tr ' ' '\n' --- --header "Expression Option (or type custom)?"

$ EXPR_SET: echo 'clock creds desc file fstat fstatfs ipc llstat memory net process pure signal stat statfs all none' | tr ' ' '\n' --- --header "Expression Set (or type custom)?"

Now we can interactively build a full strace command!

We want to allow the user to type something outside our list, because strace

supports a bunch more options, and regex, or ! not expressions, etc. However,

navi doesn't have a full way to express those options so we're limited.

But this is still leaps and bounds better than nothing!

Conclusion

Hopefully, this has shown how having a command builder can be a huge help.

Yes...it is work to make the cheat sheets, however there are plenty out there

ripe for copying. navi also has built in functionality to add public git

repos as cheat repositories, and have them automatically updated. I prefer to

use my own and have more control over them, but that option exists for those

that want to bootstrap making their own cheats.

There is quite a bit more navi can do, but this post is long enough!

Happy cheating.